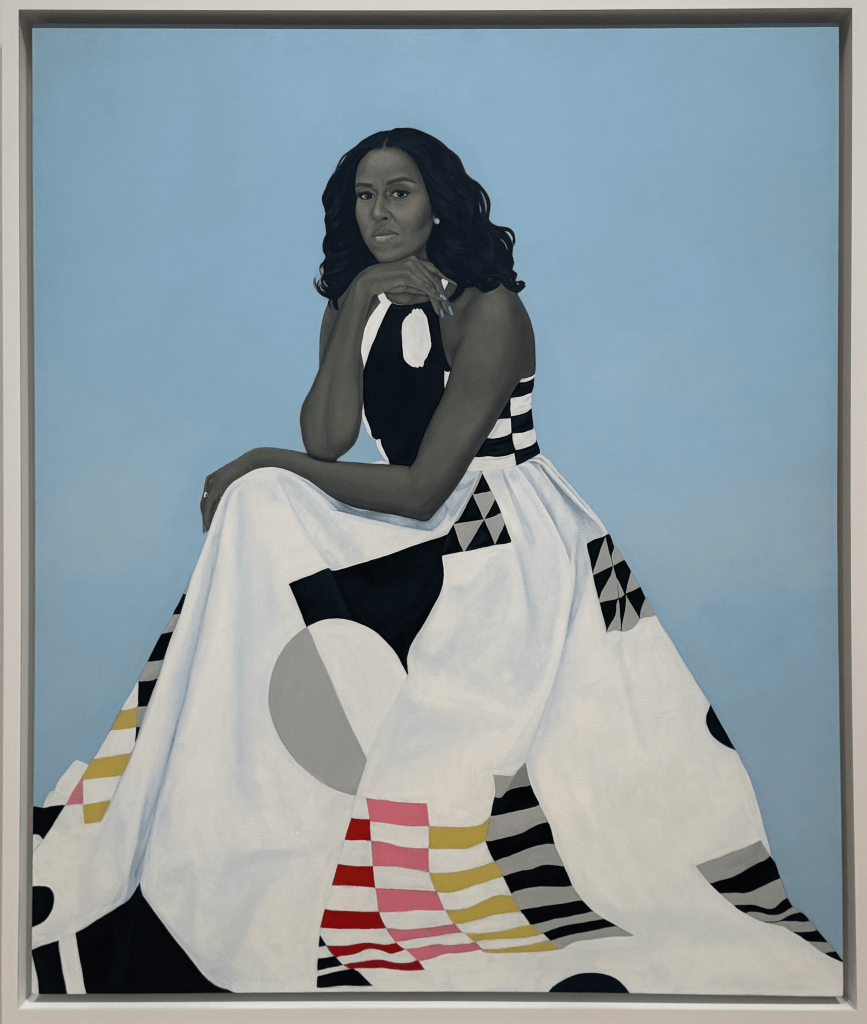

Contributed by Margaret McCann /Amy Sherald’s paintings of mostly ordinary and upright African Americans, in “American Sublime” at the Whitney Museum, transcend portraiture, vaulting to socio-political metaphor. Their evocative titles – drawn from Emily Dickinson, Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison, and other cultural figures – suggest an array of personalities or experiences. But the exhibition title, from Elizabeth Alexander’s poem of the same title, unsettles our understanding of what both figures and viewers behold. Michelle LaVaughn Robinson is one of two straightforward portraits in the show, and a personification of fortitude. Recalling mighty females of painting past – Ingres’s elegant dames, Velazquez’s princesses, the Virgin Marys of Piero della Francesca – her dress’s massive form becomes an apt visual metaphor for power, its striking design symbolically coordinating black and white, like El Lissitsky’s red and white.

Atop the mountainous gown the First Lady sits, more circumspect than relaxed, a somewhat reluctant heroine. Articulations of volume throughout the composition – modulations of anatomy, foreshortening of geometric pattern, overlap of wrist over knee – belie flatness. The Obamas’ grasp of their responsibility as trailblazers and role models shows in their choice of younger African American painters for official portraits. Sherald was selected to paint the first Black First Lady after becoming the first Black woman to win the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s competition in 2016. President Donald Trump recently decreed that Vice President JD Vance would oversee that collection, which includes both Sherald’s portrait and Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of President Barack Obama, to “remove improper ideology.”

Given her background, Sherald’s paintings can’t help but reflect the African American struggle from marginalization to prominence, emblematized by Barack Obama’s two terms as president and the Black Lives Matter movement. The elegiac Hangman, painted a year before Obama’s victory in the 2008 election, is the most cynical image in the show. The figure’s undershirt and bare feet indicate the disadvantage framed by Social Realism, the painting’s texture and verticality Gustav Klimt’s Symbolism, the piece’s mood and tonality the work of Odd Nerdrum, with whom Sherald studied. Faint text at the top resembles the macabre childhood word game in which players build a virtual gallows. The body, in profile, hovers as much as it hangs, its dissolution into figure-ground equivocation, soft brushwork, and soothing color quietly delivering the horror of lynching. Suppressed anger, like that in Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit, looms in red silhouettes that witness, warn, or mourn.

The Boy with No Past, from 2014,spreads optimism. Against an atmospheric background typical of Sherald’s early work – she studied with Grace Hartigan – upbeat colors interact. The cool blue shirt pushes the warm background toward orange, cheerful yellow brightly advances. Sherald’s lively geometric vocabulary echoes the melding of African pattern and Cubism in Jacob Lawrence’s and Romare Bearden’s interlocking gestalts as well as the art of the African Diaspora she studied under Arturo Lindsay. The smartly dressed young man steps out of any protective field, taking center stage with the poise of Antoine Watteau’s Pierrot. Lacking a past, he is unburdened, but he’s not oblivious. Eyes disguised by whimsical shades and his receding face suggest environmental psychology’s prospect-refuge theory: seeing without being seen creates the best vantage for comfort and survival. Despite their forthrightness, Sherald’s figures maintain circumspection.

Flashy or symbolic outfits, like that in What’s precious inside of him does not care to be known by the mind in ways that diminish its presence (All American), offer their own kind of social distancing. On a museum wall the figure acquires permanence, his world golden and iconic. Yet today’s “patriotic correctness” puts this cool customer at risk for his boldness. Might he naively presume the unsung role of black cowboys during and after slavery – proudly embodied in Beyonce‘s Cowboy Carter – is accepted by all Americans? He can nominally broadcast belonging, yet the high-contrast stars and stripes almost float off his shirt.

While Sherald’s figures resemble Barkley Hendricks’ more extroverted ones, their stillness has them taking themselves more seriously, perhaps now having more to lose. Cropped below the knee, installed near eye level, the work compels close encounters between figures and viewers. In What’s different About Alice is that she has an incisive way of telling the truth, the depicted photographer flips the script, making the viewer the object of scrutiny. Juxtaposed with flat color, variegated flesh softens and perhaps mediates stresses of identity and assimilation – the disorienting “double consciousness” W.E.B. Dubois described. Kerry James Marshall’s provocative stereotypes convey “presence and absence.” Sherald’s “grey” flesh pays homage to early black-and-white portrait photography’s contesting of African American invisibility, which Dubois showcased at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. Before anyone gets too somber, Sherald’s lush color harmony in easygoing shapes usher in pleasure. Fleshtones shift warm in relation to cooler blue green and lavender, but cool against warm hues, as warm oranges pop against mild colors. Working the room, Sherald’s paintings charmingly expand our view of normal.

In If You Surrendered to the Air, You Could Ride It, a man distantly eyes us, cornered between high steel beams, maybe waiting for something or deciding what to do next. He is upright and alert, as though interviewing for a job. His immediate situation recalls Fernand Leger’s confident construction workers or the iconic 1932 photograph Lunch Atop a Skyscraper, but he is alone and not dressed for work. A strange image of dislocation and silent desperation, the painting conveys the peaceful alienation of a Carlo Carra loner or statue in a De Chirico painting. In linking “American” to “sublime” without “African” in a show involving Blacks aspiring to the American Dream, Sherald introduces vexation into the context of the sublime. As Edmund Burke wrote, “terror is in all cases … openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.” Without a ladder this man looks unreachable, stuck. The clear blue sky might signal his demise; Falling Man could come to mind.

The eye moves easily and elegantly through pleasing, closely toned color shapes in Breonna Taylor, commissioned for Vogue magazine. Unlike Emmett Till‘s battered body, which his mother allowed Jet magazine to publish so his lynching would be publicized, Taylor’s tragedy spread quickly on social media. Her flowing weightlessness, like the Italian Mannerist Jacopo Pontormo’s Visitation, enables her angelic yet realistic visit with us. Sherald’s typically flat background gains spatial depth through fluid, proportional drawing akin to volumetric European painting. While adopted by Black leftist WPA painter Charles White, whose masterpieces were influenced by Mexican Muralists like David Siqueiros, the technique fell from favor owing to its use in Socialist Realism and Nazi art, and after the male, white colonial gaze was critiqued. Kehinde Wiley’s “oppositional gaze” and appropriation helped reconcile its rich tradition with contemporary concerns.

Recasting the Statue of Liberty with the immediacy of Pop Art, Trans Forming Liberty celebrates the expanding civil rights of LGBTQ+ African Americans. However unlikely it is Sherald’s exhibition will attract LGBTQ grooming or Great Replacement conspiracists, her work may well spur anxiety, either over the social risk-taking this character exemplifies or from “fear of a black planet.” This face-off offers even the most narrow-minded viewer redemptive catharsis: Burke argued that “the thrill of the sublime is that of danger courted and overcome, … not a positive pleasure but a more intense and delighting experience of danger survived.” Especially in large-scale works, Sherald not only celebrates but also confronts the reality of African American presence, agency, and variety. She may see her quiet exaltations, though camouflaging the pain of subjugation, also as offering Kantian transformation and redemption through the “joyful realization of the idea of free will.”

In For Love or Country, which appropriates a famous photo by Alfred Eisenstadt, political messaging is slowly filtered through the arabesque movement of the foreground figure’s graceful turn. Sherald says that “sublimity in Black life can be seen in our ability to persist and thrive despite … systemic oppression.” Her “American Sublime” references the tragic subtext of Hudson River School paintings that Alexander‘s poem describes: “miraculous black holes of color large enough to blot out the sun, obliterate the unending moans, to exalt, to take the place of lamentation.” While Théodore Géricault invokes politics in Raft of the Medusa, the Romantic sublime was politically neutral. But the glorious vistas it inspired in nineteenth-century American landscape painting became associated with Manifest Destiny, which led to the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans and the Civil War. The combination of probing gazes and subtle advocacy in Sherald’s “landscape of figures” moves like an aspirational rally beyond tragedy, towards Longinus’s sublime “elevation of the soul.”

In more contemplative works, small foot soldiers in what Sherald jokingly refers to as her “army” evoke uncertainty about where they stand, sliding into existential anxiety. In All things Bright and Beautiful, the neatly groomed braids and playful sundress of a girl too young to exert much power dispatch a sunny outlook. But an uneasy yellow, redolent of a Ernst Kirchner’s disquieting palette, presses in on her from behind. Her posture is doubtful, her head tipped, her right hand slightly self-soothing. Eyes shaded, she peers out questioningly, as though through the picture plane or a two-way mirror. Is some mirage dissolving and some rude awakening taking shape on her horizon – another American “dream deferred”?

In Kingdom, a young boy, like the one in Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, conquers his fear. At the top of a tall ladder, he becomes king of the mountain, but the beautifully painted slide’s bracing realism doesn’t seem to excite or reassure him or impel him to proceed. He remains distant, like the man on the beam, as if sizing up an approaching stranger as friend or foe. His brave visage summons the lost innocence of child labor. From this perspective, the title leans toward irony, one more broken American dream. Echoing a fascist fixation on art and extremist propaganda, Trump has moved the presidential portrait of the slave-trading president Andrew Jackson – who spurred westward conquest with the brutally inhumane Indian Removal Act – into the Oval Office and made himself chair of the Kennedy Center, while Vance has implied that the rights of descendants of Confederate secessionists who supported slavery outweigh those of later immigrants loyal to America’s founding principles. “American Sublime” stands as a civil show of force against today’s uncivil politics.

“Amy Sherald: American Sublime,” curated by Sarah Roberts, former Andrew W. Mellon Curator and Head of Painting and Sculpture at SFMOMA. The presentation at the Whitney Museum of American Art is organized by Rujeko Hockley, Arnhold Associate Curator with David Lisbon, curatorial assistant. Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, NY. Through August 10, 2025.

About the author: Painter and art writer Margaret McCann teaches at the Art Students League. She has shown her work at Antonia Jannone in Milan and been reviewed in La Repubblica, Corriere della Sera, and the Huffington Post. She edited The Figure (Skira/Rizzoli, 2014) for the New York Academy of Art and has written reviews for Painters’ Table, Art New England, and Two Coats of Paint.

NOTE: According to The New York Times, Amy Sherald has canceled the Smithsonian’s run of her show, citing censorship. “The artist said that she made the decision after she said she learned that her painting of a transgender Statue of Liberty might be removed to avoid provoking President Trump.” Read more.